Does Anyone Identify as Evil? by Johny Thomson, Big Think and Iain Mcgilchrist

Hello everybody,

This week we’re looking at the nature of evil with Iain McGilchrist. You can find the companion article here: The Nexus Method: How to make the most of what you learn

“Evil” is an odd word.

You can read a lot about evil. Growing up as I did on a diet of high fantasy, my days were (and still are) crammed with evil orcs, evil overlords, and good vs. evil. But, at least in my inconsequential pocket of human interaction, I don’t use the word “evil” that much. I talk about someone being an arsehole or a dickhead. I talk about cruel, mean, selfish, and bitter people. But I can’t remember the last time I called a person evil.

The thing about evil is that it’s what philosophers might call a “thick” concept in the way that “bad” is not. “Bad” is often just a stand-in for “I dislike or disapprove of this thing.” That game of cricket was bad. That curry was bad. My three-year-old smashing his brother’s Lego train was a bad thing to do.

Evil is different. Evil contains badness, certainly, but it also has a complicated, sinister marbling to it. There seems to be an unavoidably metaphysical or theological element to the word “evil.” Evil is some inky-dark force that oozes into the world. It’s the shadowy, CGI spectre that crawls across the movie screen. Satan is evil, and evil is Satan.

This is why, when I do use the word evil, I normally use it for faceless, unmeasurable, and indefinable elements — “evil” corporations or “evil” ideological systems that crush the good, everyday person. Evil is both more than badness and less distinct.

All of which leads me to offer an uncharacteristically theological question this week: What is evil? And for that, I spoke with a master in his field(s) and an emissary of the good: psychiatrist, neuroscientist, and philosopher Iain McGilchrist. As always, you can find our full conversation at the bottom.

Not quite good vs. evil

In Christian theology, there are essentially two ways to view “evil.” The first is the one John Constantine will be familiar with — one of hell, demons, and diabolical machinations. Evil is a thing—a pulsing presence in the Universe. The other view is known as the “privation of the good,” which suggests that evil is not a positive entity but rather the absence of good. So, when we talk about “hell,” we do not mean a nine-tiered hotel of eternal torture; we mean only a place without God.

Of course, this is not Mini Theology, and the philosophical question that runs parallel to this discussion is about what Immanuel Kant called “the good will.” A good will is what inclines a person to do the right thing. If presented with the prospect of stealing some money or handing it to the staff, which one do you choose? Kant argued that all normal and healthy human beings would always incline to the good. Humans are naturally propelled to do the right thing.

Kant was not some Indian prince living out his days in a pleasure garden; he knew the world was full of immorality. So if humans are supposed to always want the good, why do they do bad? Well, there are two answers. First, they incorrectly use their reason. They think they’re doing good when they’re actually not. The imperial invaders who think they’re bringing civilization and progress, the lying politician who thinks deceit is better for the country, and the abuser who hits their partner “for their own good” are all wrongly reasoning their way to the “good.”

The second answer is to consider those who are not normal and healthy. These are the people who not only don’t reason properly but are incapable of doing so. Many philosophers and psychologists like to refer to criminality as a kind of pathology, where, for example, murderers are seen as psychopathic or neurologically “broken” in some way. The real-life corollary of this position is to have legal systems that emphasize rehabilitation and prevention more than anything else.

McGilchrist isn’t so sure. McGilchrist argues that evil can be a thing in its own right — something that has a “drive” and “energy” — but he also doesn’t accept that evil is some kind of oppositional force to the good. “The one thing I don’t think,” he put it, “is with the Zoroastrians that there are these two equal principles of darkness and light, good and bad, and that they’re forever in war.”

So, if evil is its own thing but is also not a dualistic other side to goodness, then what is it? Well, McGilchrist offers an interesting way out by asking us to define what makes something evil and what makes something good. And here he gives a simple answer: “Love is what, effectively, the power of good represents, and hate, which is what the power of evil represents.”

In other words, that which is done from love is good, and that which is done from hate is evil.

Once we have turned the issue into being about love and hate instead of good and evil, new questions then emerge: Which is the stronger force? And what best defines the world and human nature?

McGilchrist is not overtly this or that religion, but his answer is certainly faith-adjacent. He said: “Love and hate are not equal in that love can encompass hate. It can, as it were, embrace hate and neutralize it, whereas hate can’t embrace love and neutralize it.”

This faith in the power of love — and it does feel like something akin to faith, or at the very least, hope — is not unique to any one tradition. It features prominently in Christianity’s “God is love” and “love your enemies,” certainly, but it’s also in Buddhism’s “three poisons” of hate and the loving-kindness of metta. It’s found in Gandhi’s Satyagraha (soul-force) and Daoism’s “softness overcomes hardness.”

To say love is stronger than hate and that an open embrace is more powerful than a closed fist is a bold thing to say. To hold that love is the ultimate force in the world and that it’s the source of all goodness is a belief — if not of any one religion. To believe in love is to have faith and, as with all faith, not everyone will agree.

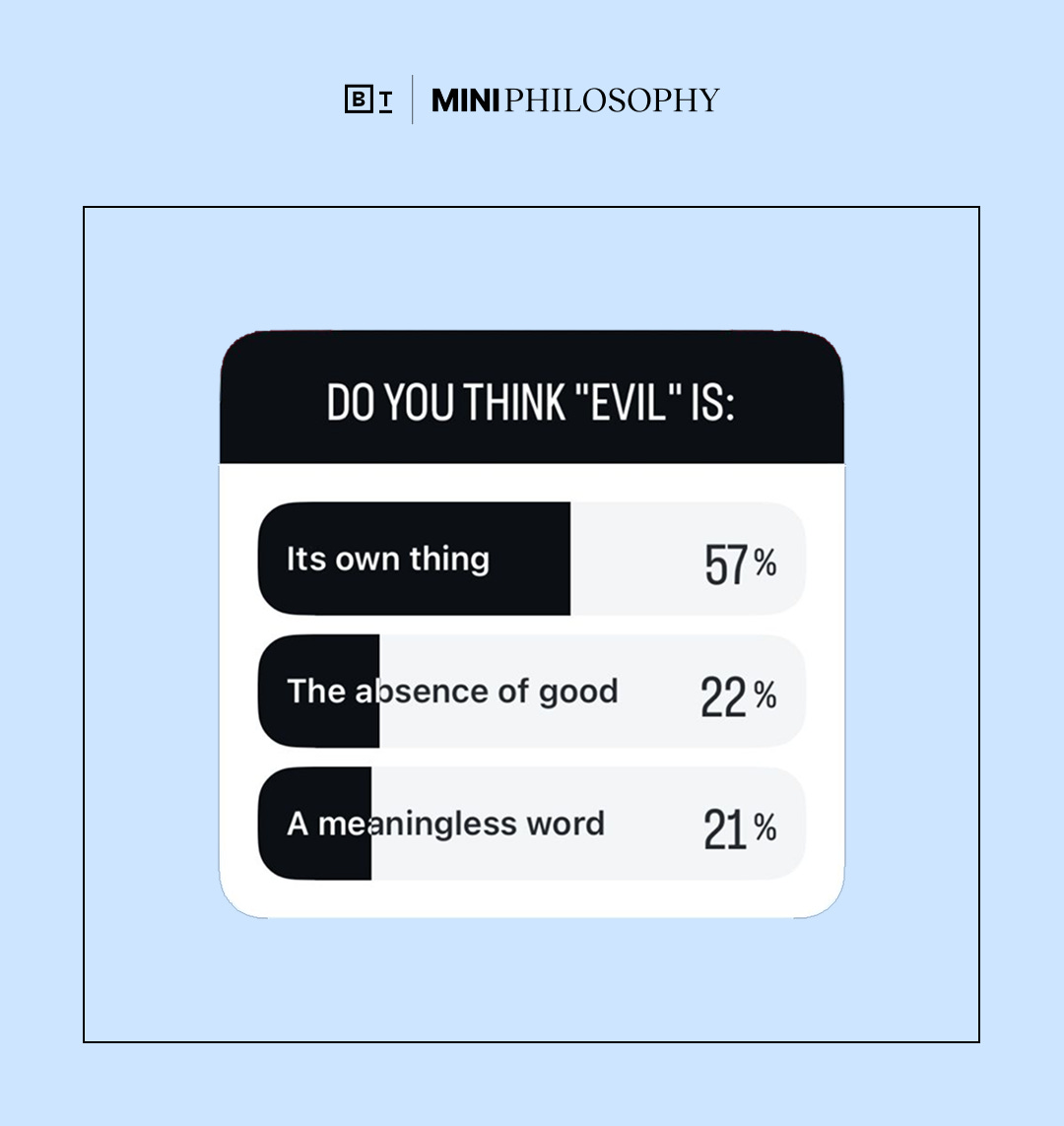

IN YOUR OPINION

An interesting answer to the poll this week. Of course, with an issue like that, my limited social media options weren’t ever going to cover the entire gamut of answers. But one answer really did stand out to me. This was sent over DM via Instagram and edited only slightly:

“You don’t define evil, you know it. It’s like the color yellow. You don’t say, ‘What is yellow?’ You know it’s yellow. You might know it’s yellow because it’s not blue or it’s not green, but it’s still yellow. Yes, evil is not good and it’s not God, but it’s also a thing. You know it because it walks into the room. You know it because it talks to you. You know it because you feel it.”

I love this answer, even if I’m not sure I’m entirely on board with it. I don’t think that I have ever had that kind of evil awareness. I’ve never felt evil walk into a room or talk to me — but that might be my gilded, genteel Oxfordshire life. What do you think?

RESOURCES

This newsletter contains my reflection on the topic at hand. Here is a list of the material shared in this email, as well as extra content about the topic that I’ve shared on my other social platforms:

-

The companion article inspired by my conversation with Iain McGilchrist.

-

My short video exploring how we define evil, featured on Mini Philosophy’s Instagram page

-

The full, unedited audio interview with Iain McGilchrist:

Jonny is the creator of the Mini Philosophy social network.

He’s an internationally bestselling author of three books and the resident philosopher at Big Think. He’s known all over the world for making philosophy accessible, relatable, and fun.