Bread cast on the waters – Iain’s Substack

I have just returned home from attending the ARC conference and giving a lecture to the Cambridge science society, the Larmor Society. Opening my post, I found a parcel sent on by my agents, which contained a recording (both CD & LP) of jazz, in part inspired by my work (I gather) from Orlando le Fleming called ‘Wandering Talk’; a book of mandala-like black and white designs, with accompanying poetic reflections, called ‘Randalas’ from Peter Pitzele, apparently also inspired by my work; and a book linking my thought with quantum biology by Brad Sampson, called Find-Your-Map. I am delighted to say that I do often receive works of art and books in some way inspired by my work, and I was given half a dozen other precious gifts just at the conference; but I mention this parcel mainly because it is a compressed expression of the wonder I feel in seeing my thinking alive in so many forms: music, art, poetry, scientific philosophy — and all in one box!

I am kept going by the kind spirit of so many people who see something worth taking on board in my work. I was moved to see that Orlando put these words from Chapter 15 of TMWT on the cover of the record:

The beauty and power of art and of myth is that they enable us, just for a while, to contact aspects of reality that we recognise well, but cannot capture in words. It is precisely their multi-layered, sometimes paradoxical meaning, well beyond articulation, that gives them value, and makes them resonate with us at so many different levels and in so many different ways. The more important something is, the more we have to struggle in the attempt to reduce it to language. We would be lost without words, but sometimes it is wisdom to be lost for words. Words are always a representation in terms of something else. The work of art exists precisely to get beyond representation, to presence, even if that presence is itself composed of words, as it is in poetry. If this were not so, a lot of effort could have been spared, as it could all have been better stated in prose. The work of art does not hide, represent, or body forth something else, that must therefore be decoded: it is precisely what it is. And yet neither is it opaque, as though we were stopped at its frontiers. It is semi-transparent, translucent: we see it all right, and yet see through it to something beyond.

I hope it won’t seem invidious to single out a few expressions of my work by established artists, from all the beautiful gifts I have received, because it is a shame not to share them. I think they are outstanding. The first is a brilliant piece entitled ‘The Master and his Emissary’, by the British painter Rob McPartland, given to me in 2010:

Then there is this magnificent sculpture by the Canadian artist David Robinson, called Corpus Callosum, made in 2019. It is a gigantic work, and this is a photograph of it:

And these are two exquisitely beautiful glass sculptures by the British artist, Jackie Henshall, called ‘forest contemplation’ and ‘sky contemplation’ and made in 2024 (in real life, if not in my photograph, they are exactly equal in size

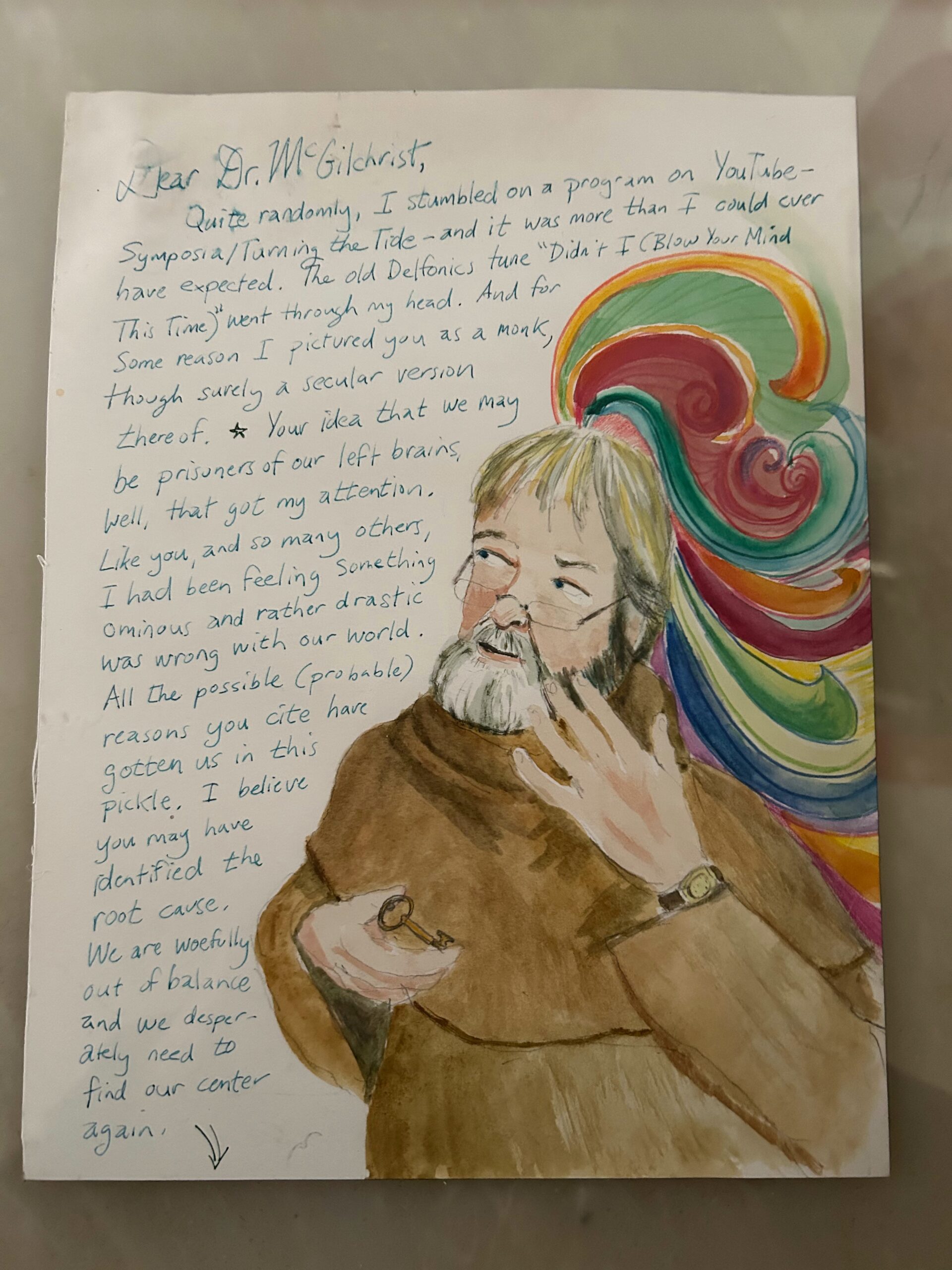

Finally, for fun, I include this witty sketch by an American correspondent, which picks up on my lightly cloistered tendencies … but notice the key: is this key that gets me out of the cloister? or let me in? or the key that was set to ‘remain forever where the locksmith made it, and never be used to open the lock the Master forged it for’ – a quote from Wittgenstein with which I open the Introduction to TMWT:

I have not mentioned his name because he might not wish it, but if he reads this and doesn’t mind, I’ll make the author known. And of course I have received many other wonderful gifts of poems, embroidery, and much else, which are no less special to me — but we have to stop somewhere.

More on mechanism in biology

Mike Levin’s paper:

And here is my response:

I think the idea that there is a drive of some kind that is behind the physical realm, that as you put it ‘ingresses’ into the phenomenal world and finds expression there, is surely right. As you recognise, Jung’s idea of archetypes is a way of expressing the idea that there exist non-instantiated forms that are capable of instantiation and in some sense call forth their embodiment. Your other quote from Jung – ‘The artist is … one who allows art to realize its purposes through him’ – is an expression of an experience we may all have of being worked through by something bigger than our conscious intention – even in dance or music, at a humble everyday level, but also in creations of a more cognitively complex kind.

You say ‘cognition is a continuum’, and this is part of a panpsychist position that is surely right. Continuity is everywhere in cosmology and biology: it tolerates but subsumes discontinuity. As physicist David Tong says, ‘At a fundamental level is nature discrete or continuous? I see no evidence whatever for discreteness. All the discreteness we see in the world is something which emerges from an underlying continuum …’

You say ‘mind precedes, and is a superset of, life’. I would agree. [Note for readers: I discuss the nature of consciousness and its relation matter at length in Chapter 25 of TMWT.] However I notice that your remark that ‘the story of the self-assembly of the body and its emergence from a formless chemical chaos shares a deep symmetry with the emergence of minds from a mindless void’ is somewhat in conflict with other remarks you make which implicitly or explicitly suggest there is ‘mind in everything’ (as Heraclitus maintained): ‘a kind of panpsychism is unavoidable’, ‘there are no truly inanimate systems anywhere – they all reflect patterns from the same unimaginably rich pool’. All of which I would agree with. Thus I don’t think mind ‘emerges’ (what kind of a miracle would that be?) from a mindless void, but is indeed an ontological primitive.

I also think Platonism might not be the best sort of philosophy to invoke. I know your caveat is that you want to use already familiar terms rather than multiply terminology. But in this area a term like Platonism can derail things. Plato’s ideas were of perfect, static abstractions of which anything in the phenomenal world was a mere copy. This lacks the potential that is in dynamism, and the idea of ‘being in the process of evermore coming into being’. Aristotle might be a better guide, with his all-important idea of final causes – these are surely the goals towards which systems are drawn from in front – not impelled mechanically from behind: as you say ‘many biological patterns are goals the system pursues, not mechanical outcomes’.

My conviction is that the whole cosmos has a drive towards bringing about something new, is creative, and in the process is not so much pushed forward, but drawn forward by purpose and values. It does not just push forwards regardless. There are lures, attractors, that ‘pull’ things forward. It is unfortunate that biology has been hobbled for so long by the need to deny both purpose and value, since these are an important part of the picture. I don’t know if you would agree.

You ask ‘what if some of the Platonic patterns that matter for biology are, themselves, intelligent to a degree?’ I think this is important. The fact that this lure and whatever is attracted to it are part of one intelligence is so beautifully illustrated by the many deeply thought-provoking examples you give: ‘biological wholes have the ability to achieve specific patterns despite novel conditions’, etc: And you say at one point: ‘This is impressive enough, but the truly remarkable thing happens when the cells are made so large that only one of them fits into the diameter of a normal tubule. In that situation, single cells wrap around themselves to make the same structure.’ This is surely extraordinary in its clear expression of ends generating novel and intelligent means. I wholly agree that there is a ‘pole star that guides its activity – the attractor in morphospace to which it must find a path’. I love that the algorithms display ‘delayed gratification’. This effectively means that the process can ‘see ahead’, as it were around obstacles, over a rise in the road. If this were not possible life could never have come into being before it yielded to entropy.

You draw attention to the ‘remarkable and beautiful (also life-like) pattern seen in the Halley plot kinds of fractals. That entire highly specific form is encoded in the very simple formula in complex numbers, and can be revealed by a simple algorithm. The fact that this highly complex pattern is indicated by a very short description of a function provides an un-ending richness from a small seed.’ For me this word ‘seed’ underlines two important points: one is that of potential, which is crucial: the potential for beauty and complexity within what appears simple. I consider this a perfect example of a cosmos creatively unfolding its potential. And the second is that this potential discloses beauty and order, not valueless chaos. You several times refer to ‘patterns that ingress in a way that results in getting more out than we put in’: I think this expresses exactly this fulfilment of potential.

The importance of potential is vital. Everything is developing and changing, moving forward in the continuum of flow. You refer to the key question of ‘where these patterns come from’. To me the only way of seeing this that makes sense is that they are part of the purposes of whatever underwrites there being anything at all – namely the ground of being, aka God (I know, I know!) I see that ground as being infinite potential, that is in a process of self-discovery by actualising itself. I think this is something like Whitehead’s view. We are part of this process, a partner in a reciprocal dance, and we are different from inanimate matter only in the (vast) degree and nature of our capacity to respond, to reflect, to enable a resonant relationship with ground of being. (I think this is not something you can say in a conventional biological paper – but they are my thoughts for what they are worth.)

Everything is relational. Nothing exists that is not a relation. It is the dipole of the ground-of-being in relation with what-is-coming-into-being that allows everything that is to come into being at all.

A comment from the perspective of hemisphere theory. You write:

‘Consider the classic liar paradox, in which sentence X says “X is false”. Patrick Grim developed a fascinating perspective on this by doing two things. First, he added an element of time: there is no paradox if we allow the truth value to change and consider the time-extended behavior; the paradox arises from our trying to freeze a fundamentally dynamic pattern down into an assumption that a proposition should have a static truth value (not move in the abstract space of logical sentences). Second, he moved to fuzzy logic, to allow the Boolean true-false cycle to take on more interesting shapes by allowing sentences like “X is 80% true”. Finally, he enlarged the space by considering and plotting the structures formed by sets of N mutually-referencing sentences. This allowed him to observe complex, dynamic, often fractal patterns corresponding to logical sentences. That extends the flat world of static truth claims to a domain of interacting, rich, time-dependent systems.

These are topics I have discussed at length in The Matter with Things (esp in Chapter 16), the reason being that the paradox arises because of the cognitive pattern associated with the left hemisphere. Amongst its characteristics is its collapsing of time (because it thinks in abstractions where time does not operate, and has no grasp of time as experienced, which is something the right hemisphere alone appreciates [Note to readers: time is central to my argument in TMWT, and is the topic of Chapter 22]. Secondly it has no grasp of degrees of truth. Thirdly it flattens space into two dimensions. Most of this is in Chapter 16 [Note to readers on spatial depth and the RH, see also Chapters 2 & 3]. Why is it relevant here? Because the two hemispheres embody two distinct drives and two different sets of values. And I believe they antedate their instantiation in the human brain. The drive of the left hemisphere is towards grasp and utility, and the closing down of potential into a certain actuality; the drive of the right hemisphere is towards higher non-utilitarian values, such as goodness, beauty and truth. Now, that is at the human level comprehensible, but this pair of drives goes, in my view, right the way down in cognitive structures to the lowest level. One (L) is the force for explicitness, division, actuated potential; the other (R) is the force for implicitness, wholeness, actuating potential. I can demonstrate at the level of human neurology that there is a movement from R, to L, and then back to R again. This I believe is an analogue of Whitehead’s idea of potential becoming actual, and thus losing some of its power, but that the product nonetheless takes its place again in the now increased field of potential.

Finally the ethical matter that we don’t know what it is we are making seems to be related to this. You rightly refer to ‘ethical lapses’; and refer to the need for ‘considerable humility with respect to our engineered constructs … because much as with the eons of competence without comprehension around having babies, we can make things without understanding how it works or what we really produced.’ You say ‘we must be open to surprises and treat our constructions with care’. This aspect cannot be overstated, and again invokes value. The question is what values and purposes guide each development. Are they driven by the lowest level in Scheler’s hierarchy of values, utility for power, or towards the fulfilment of the highest, the sacred values of beauty, goodness and truth? And this might sound as if I mean simply ‘what is in the mind of those doing the experimental work’. That certainly comes into it: but I am thinking of the level at which there is what you call an ingressive form. Ultimately I believe these are just different levels of a holographic entity.

—

Mike is a developmental and synthetic biologist at Tufts University, where he is the Vannevar Bush Distinguished Professor, amongst other things.